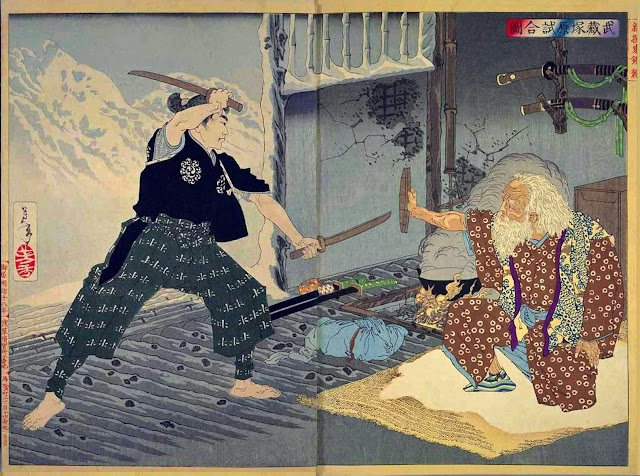

(Miyamoto Musashi fighting Tsukahara Bokuden, painted by

Yoshitoshi (1839–1892), [Public Domain]

via Creative Commons)

Around 1584 CE, a boy was

born into the Hirata family of samurai in the village of Miyamoto, located in

the Harima Province of Japan. The boy’s father, Miyamoto Munisai (or Shinmen

Munisai), was considered to be one of Japan’s greatest swordsmen, and he ran

the village’s local dojo. With such a skilled parent, many would have expected that

the boy would grow to be skilled with a sword. Yet, few could have predicted

the unprecedented martial prowess that the newborn child would soon show the

world. The boy’s name was Miyamoto Musashi, and he would later claim to have

fought in over sixty duels, many of which ended in the death of his opponents.

Although Musashi is best

remembered for being the undefeated “Alexander the Great” of dueling, he was

also a bit of a renaissance man. Besides being a duelist, he joined the

military and fought in around six battles. He also was an artist who painted,

sculpted and carved. As another occupation, he became a foreman or supervisor

and worked in construction. Yet, his greatest contribution to his legacy was

his writing career.

When he was around twenty-two

(perhaps, 1606 CE) he produced his Writings

of the Sword Technique of the Enmei Ryu (Enmei Ryu Kenpo Sho), which was his first known written work on

swordsmanship. In addition to this, near the end of his life, he also wrote the

Thirty-five Instructions on Strategy

(Hyoho Sanju Go). All his earlier

writing, however, were surpassed by the book he wrote in the years preceding

his death in 1645—The Book of Five Rings,

or Go Rin no Sho.

Nevertheless, Musashi’s

careers in literature and construction are not why most readers are here,

reading this article. No, the most interesting and dramatic events in Miyamoto

Musashi’s life came about because of the decades he spent wandering Japan as a

traveling duelist.

(Snowball Fight, by Torii Kiyonaga, from the series Children at Play in

Twelve Months, 1787, woodblock print, Honolulu Museum of Art, accession 15966,

[Public Domain] via Creative Commons)

In 1596, the

thirteen-year-old Miyamoto Musashi was living a quiet life with his uncle in a

temple located in Hirafuku, but his future was about to change drastically. As

Musashi was walking the streets of Hirafuku, he saw a posted message that

caught his ever-attentive eye. The public note was a challenge issued by Arima

Kihei, a traveling samurai. In the note, Kihei challenged anyone to test their

mettle against him in a duel. With this samurai’s notice, the cogs of fate

began to turn for Miyamoto Musashi.

(Portrait of Miyamoto Musashi by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798–1861), [Public Domain] via Creative

Commons)

There was no way anyone could

have assuredly predicted what would happen next. Sure, Musashi was the son of

one of Japan’s most skilled swordsmen, and he had even trained for a short time

in his father’s dojo. Yet, he was still just a thirteen-year-old boy with a

stick, facing down a samurai warrior. He could not possibly win. Nevertheless,

win is exactly what Musashi did.

The duel was apparently over quickly.

The young boy knocked the samurai off his footing. Then, the thirteen-year-old

Musashi proceeded to savagely beat Arima Kihei to death with his stick. Before

even settling into puberty, Miyamoto Musashi had already killed a man.

(Sekigahara Kassen Byōbu (『関ヶ原合戦屏風』), Japanese screen depicting the Battle of Sekigahara

(関ヶ原の戦い),

c. 19th century, [Public Domain] via Creative Commons)

In 1599, at around fifteen or

sixteen years of age, Musashi decided to leave home and explore Japan. It was a

chaotic time, to say the least. The military leader of Japan, Toyotomi

Hideyoshi (1537-1598 CE), had just died without a proper heir, leaving a perfect

power vacuum available to be exploited by anyone who had the means and ability

to seize power. Two major factions formed: the unstable remnants of the

Toyotomi clan and its allies, against the powerful forces led by the daimyo

(feudal lord), Tokugawa Ieyasu. The Miyamoto samurai were pulled into the war

by their liege, the Shinmen clan, which sided against the Tokugawa. During the

war, Musashi joined with his liege’s forces and participated in some of the

battles. Most notably, he is thought to have been present at the Battle of

Sekigahara in 1600 CE—the battle that cemented Tokugawa’s dominance in Japan. With

the Toyotomi forces suppressed for the time being, and the Shinmen daimyo in

hiding, Musashi became a rōnin (a samurai without a master) and took to the

road, beginning a long string of famous duels.

By 1604, Miyamoto Musashi

made his way to the city of Kyoto. The young duelist entered the city with a

specific task in mind—he wanted to duel the elites martial artists from the

Yoshioka School. The head of the school, Yoshioka Seijuro, accepted the

challenge, and agreed to meet Musashi for a duel, with the condition that each

warrior would be allotted only one blow.

Seijuro arrived for the duel

at the designated time and place, but Miyamoto Musashi was nowhere to be found.

In fact, Musashi was using one of his specialties—psychological warfare. By the

time Musashi arrived with his signature wooden sword (or bokuto), Yoshioka

Seijuro was confused, frustrated and anxious. As stated earlier, each duelist would

only attack once, but that was ample enough opportunity for Miyamoto Musashi to

secure victory. He brought down his wooden sword with enough strength and

precision to break Seijuro’s left arm and completely cripple the shoulder. Musashi

undisputedly won the duel.

After the fight, Seijuro

reportedly decided to spend the rest of his life as a monk, and handed

leadership of his family and school to his brother, Yoshioka Denshichiro.

Looking to regain lost honor for the Yoshioka family, Denshichiro challenged

Musashi to another duel—this time to the death. Denshichiro arrived for the

duel, wielding a staff reinforced with steel rings. Miyamoto Musashi, once

again, arrived strategically late, carrying his trusty wooden sword. When the

duel began, Denshichiro was completely outmatched. Legend claims that Miyamoto

Musashi killed his opponent with a single blow to the head.

(Miyamoto Musashi painted by Yoshitaki

Tsunejiro c. 1855, [Public Domain] via Creative Commons)

After escaping Kyoto,

Miyamoto Musashi traveled to Nara, where he dueled spear-wielding warrior

monks. He eventually decided to travel to the new Japanese capital city of Edo

around 1607 CE. While on the road, he dueled to the death with a man named

Shishido Baiken, who wielded a kusarigama, a sickle or scythe attached to a

long chain. This duel, like all others past and future, ended with Musashi as

the victor. Within the same year, Musashi was challenged to a duel by another

undefeated duelist named Muso Gonnosuke. The two both fought with wooden swords

and Musashi emerged victorious. Gonnosuke survived the duel and studied his

loss carefully, refining his technique. Gonnosuke and Musashi fought a rematch

years later and, despite Gonnosuke’s improvements, Musashi proved to be unbeatable.

(Depiction of Sasaki Kojiro dueling Miyamoto Musashi, by Ashihiro

Harukawa c. 1810-1820, [Public Domain] via Creative Commons)

War, Dueling and Legacy

From 1614 to 1615, Miyamoto

Musashi is thought to have rejoined the Toyotomi forces in their continued

struggle against Tokugawa rule in Japan. The Tokugawa, deciding to subdue their

rivals once and for all, besieged Osaka Castle, the center of operations for

the Toyotomi. It is generally assumed that Musashi was aiding the Toyotomi

during the siege, but his military career during this time remains vague. Nevertheless,

after the fall of Osaka in 1615, Miyamoto Musashi somehow befriended the Tokugawa

regime, even after having fought against them several times during his life.

(Miyamoto Musashi (1584-1645), Shrike Perched on

Bamboo, [Public Domain] via Creative Commons)

(Miyamoto Musashi (1584-1645), Wild Geese and

Reeds, [Public Domain] via Creative Commons)

(Self-portrait of Miyamoto Musashi (c. 1584 – 13 June 1645), [Public

Domain] via Creative Commons)

Even though Miyamoto Musashi

had found himself new professions, hobbies and even a newly adopted family,

Musashi’s dueling career continued. Around 1621, he dueled at least four men in

the region of Himeji. The most important of his opponents was named Miyake

Gunbei. After the duels were concluded—as always, with Musashi victorious—the

master duelist decided to stay in Himeji. While there, he used his skill in

construction to help with the development of the town. Musashi’s adopted son,

Mikinosuke, even became a vassal of a local lord in Himeji.

(Miyamoto Musashi from a Japanese scroll, [Public Domain] via Creative

Commons)

One year after the death of

Mikinosuke, Musashi began, once again, to resume his familiar travels

throughout Japan. He eventually settled

down with his other adopted son, Iori, in either 1633 or 1634, in the region of

Harima. There, he continued his duels—he defeated a prominent warrior named

Takeda Matabei, who specialized in the lance. Also, when the

Christian-influenced Shimabara Rebellion erupted in 1637, Musashi helped his

son and the Ogasawara daimyo defeat the rebels by offering advice on military

strategy and management.

In the last decade of his

life, Miyamoto Musashi began writing down more of his fighting technique and

philosophy. In 1641, he wrote the Thirty-five

Instructions on Strategy (Hyoho Sanju

Go), which would serve as a rough draft of his next and greatest work.

Finally, after he began to suffer bouts of neuralgia, Musashi retired in 1643 to

live in Reigandō, a cave located in Kumamoto, Japan. There, it is said that he

worked on his masterpiece, The Book of

Five Rings (Go Rin no Sho), until

the last year of his life in 1645. A simple read and short in length, The Book of Five Rings can be easily

underestimated. Yet, like its author, Miyamoto Musashi, the little book

overflows with unique skill and insight.

Written by C. Keith Hansley.

- The Book of Five Rings by Miyamoto Musashi, translated by Lord Majesty Productions, 2005.

- http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Miyamoto_Musashi

- http://www.biography.com/people/miyamoto-musashi-38201

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Miyamoto-Musashi-Japanese-soldier-artist

- http://www.musashi-miyamoto.com/musashi-duel-years.html

- http://www.kampaibudokai.org/MusashiArt.htm

No comments:

Post a Comment